In June 1838, Westminster Abbey was at the centre of the empire’s attention as the coronation for the new, young Queen approached.

George Giles Vincent, the Abbey’s Chapter Clerk, would have been heavily involved with the preparations for the momentous event; along with the Clerk of Works, who oversaw the construction work, and the Duke of Norfolk, who was busy with the administration.

Mr. Vincent's youngest child, nine-year-old Emilia was surely caught up with the excitement of the great occasion;

Westminster Abbey from Dean's Yard. Drawing by Herbert Railton

from the first wagonload of timber arriving at the great doors, the rattling and banging of scaffolding, and the building of the tiered galleries that would protect the monuments from damage and eventually seat 7,000 spectators, plus 400 or so musicians, choristers and officiants.

After the building work, the decorations. The abbey was transformed into a lavish theatre with hangings of scarlet and purple with gold trimmings, coats of arms, and extra lights.

Emilia was no doubt forbidden from entering the Abbey while construction was going on, but perhaps she and her friends played some lovely games in the cavernous spaces created by the erection of the banks of seating; spaces that would later accommodate long tables for serving refreshments.

In front of the west door, a temporary gothic style portico appeared, beautifully furnished and carpeted, with rooms either side for the reception of the Queen and her royal entourage.

The whole of the capital was gearing up for celebration; the surrounding streets were being festooned with colourful banners and bunting, and gas-lit illuminations were appearing on surrounding public buildings.

A huge fair was being set up in Hyde Park and all along the streets along the procession route, anyone who owned a house or even a tiny piece of land was building a bank of seating on it and selling tickets. Seats at prime positions near the abbey were being sold for as much as two guineas apiece.

Mr. Vincent, like his neighbours, hoped to make a little money. For the coronation of Victoria’s uncle, King George IV in 1821, Mr. Vincent had rented out the space in front of his own house in Broad Sanctuary to two builders, who erected a bank of seating; on the condition that they did not obscure the view from his own windows. He also allowed ladies using the seats to walk through his house to use the privy. He may well have done the same in 1831 and 1838.

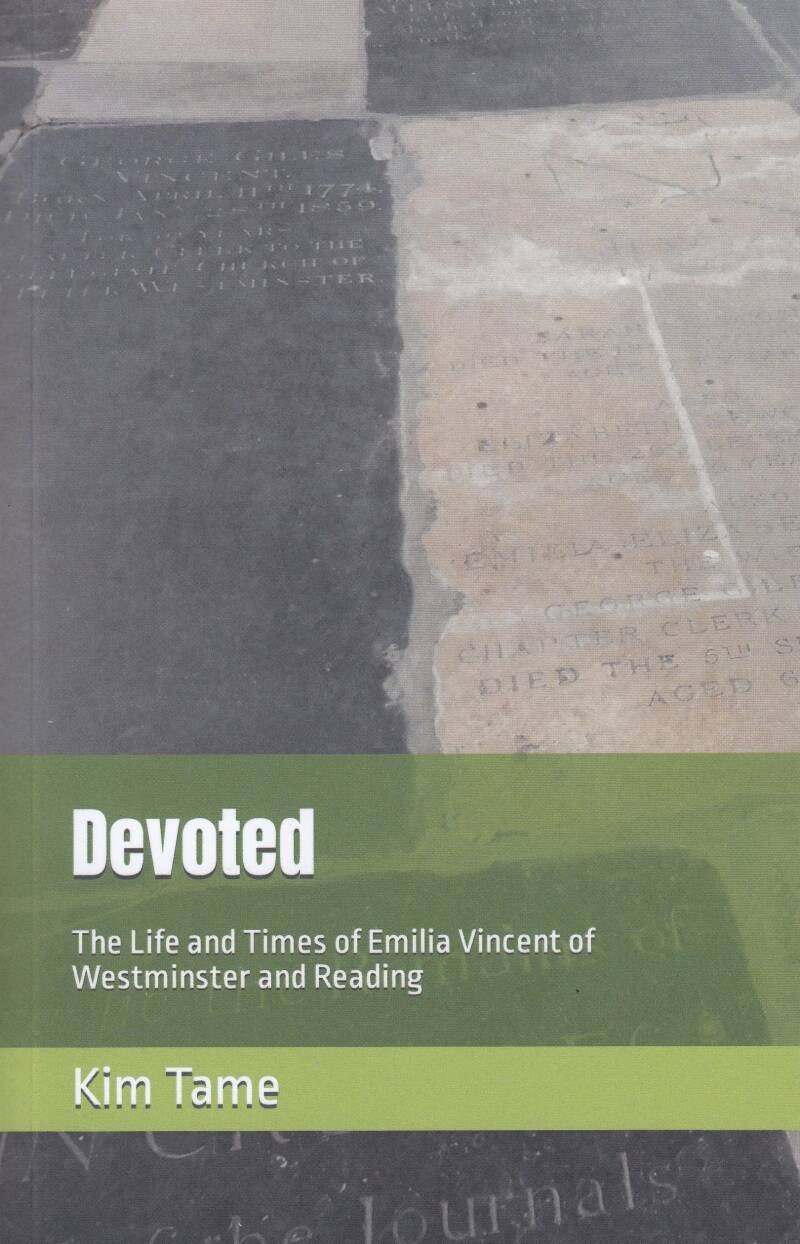

There may well be evidence of the seating stand itself, in this picture here . (The houses shown were demolished, and the gothic terrace which now forms Broad Sanctuary was built.)

Queen Victoria making her coronation oath. Painting by Sir George Hayter

At the centre of it all was the spot where the ceremony was to take place, and the 19-year-old Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent would be crowned Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

For the Vincent family, the excitement of this major event was tinged with sadness; Emilia’s maternal grandmother, Margaret Tappenden, a frail old lady of 86, had died that week. But those family members who attended the coronation had to put aside their mourning clothes for the duration; only court clothes and evening dress would be allowed in the Abbey.

Emilia herself was likely to be at home, with the servants and other family members not able to get a seat in the abbey. From the vantage point overlooking Broad Sanctuary, adjacent to the west door, those at home could watch the arriving processions, perhaps following the order as published by the London newspapers and working out who was who amongst the foreign ambassadors, regiments of troops, bandsmen and British nobles.

At last, the queen’s party of twelve carriages arrived, with escorts, ladies-in-waiting, gentleman ushers and grooms, with Yeoman of the Guards riding or walking alongside. Finally, the state coach, drawn by eight cream-coloured horses, attended by a Yeoman of the Guard at each wheel, and two footmen at each door, and followed by a final squadron of Life Guards.

Later that evening, nearly every government building blazed with colourful gas-lit illuminations. Crowns, stars, laurel wreaths, “Victoria Regina” or “VR” shone out from Somerset House, the Home Office, the Admiralty, East India House, Custom House, Excise Office, the Mansion House, the Bank of England, the Guildhall, Goldsmiths’ Hall, Mercers’ hall and many other buildings.

The festivities continued for several days, with exciting events all over London.

At Vauxhall pleasure gardens, a grand coronation gala included the intrepid aeronaut, Mr. Green, demonstrating his hot-air “Nassau Balloon ”.

In Hyde Park, a spectacular fairground covered about 50 acres, and accommodated nearly one thousand booths and stalls, including swingboats, clowns, acrobats, food and drink and a pyrotechnic show.

At length, the excitement died down. Workmen returned to Westminster Abbey to dismantle the theatre and reveal the memorials once more. The Hyde Park fair was packed away and removed. The decorated streets returned to normality and the abbey to its everyday calm.

Emilia Vincent was to live through the entire reign of Queen Victoria, and witnessed the major changes and challenges of that era; and even lived long enough to remember the next coronation in 1903.

Add comment

Comments